Home » Posts tagged 'Some Habits and Customs of the Working Classes (1867)'

Tag Archives: Some Habits and Customs of the Working Classes (1867)

The Isle of Dogs by Thomas Wright 1867

Workers in a Isle of Dogs Foundry mid 19th century

Thomas Wright (12 April 1839 – 19 February 1909) was an English author who wrote predominantly about the working conditions in England.

What made him unusual was he was a working man himself, travelling around finding work as a labourer in a engineering firm. Even when he became a writer he was known as the ‘The Journeyman Engineer ‘.

He was mostly self taught and had a number of books published, his most popular being Some Habits and Customs of the Working Classes (1867), The Great Unwashed (1868), and Our New Masters (1873).

The following essay is from Some Habits and Customs of the Working Classes when he visits the Isle of Dogs and describes the industries and the considerable Scottish influences.

Building the Millwall Docks 1867

One of the most interesting, and in many respects representative of these little known districts, is the Isle of Dogs. “The island,” as it is familiarly called – although properly speaking it is a peninsula – is not very pleasant in its physical features. It is situated about six miles below London Bridge, and lies considerably lower than the level of the river, which is only prevented from overflowing it by strong embankments. As owing to its exceedingly low level it cannot he efficiently drained, it is very marshy; broad ditches of filthy water running on each side of its main road. To a casual observer it would appear that a visit to the island could only be interesting to persons who wished to study a peculiar style of dwelling- house architecture, the effect of which is that a dissolution of partnership takes place between the woodwork and brickwork of the lower stories before the upper ones are built; or to antiquarians desirous of seeing what the roads of England were like before Macadam was born or commissioners of paving created. And while its slushy, ill-formed roads, its tumble-down buildings, stagnant ditches, and tracts of marshy, rubbish-filled waste ground make the outward appearance of the island unpleasant to the sight, chemical works, tar manufactories, and similar establishments render its atmosphere equally unpleasant to the olfactory sense. Nevertheless, there is much that is interesting in the Isle of Dogs. I have somewhere seen this district described as the Birmingham of London; but I think that the “Manchester of London would convey a much more accurate idea of the kind of place the Isle of Dogs really is.

But in the Isle of Dogs, as in Manchester, the articles manufactured are large, important, and of an eminently utilitarian character.

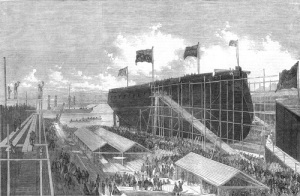

Launch of the Northumberland 1866

On “the island” is centred the iron ship building and marine engineering of the Thames. There are more than a dozen ship and marine engine building establishments upon it, amongst them being the gigantic one in which the operations of the Millwall Iron Works Company are carried on, and in which the Great Eastern, the large Government armour-plated ram Northumberland, and many other of the largest merchantmen and vessels of war afloat have been built. Here, too, a great portion of the armour-plate with which our own and foreign nations are encasing their ships of war, and with which the coast defences and other fortifications of Russia are being strengthened, is manufactured. The works of this company alone employ on an average 4000 men and boys, and the other ship and marine engine works on the island employ from 2000 to 100 men each. It would be within the mark to say that the shipbuilding and marine engineering of the Isle of Dogs gives employment to 15,000 men and boys; and, in addition to these shipbuilding establishments, there are on the island tar, white-lead, chemical, candle, and numerous other factories, which afford employment to a large number of men. There are two townships on the island-namely, Cubitt Town and Millwall, and it is in the latter place that a major portion of the manufactories of the island are situated; and Millwall is the place usually indicated when “the island” is spoken of by the inhabitants of the locality.

Any person having a practical acquaintance with the construction of iron ships would naturally expect to find a sprinkling of Scotchmen among the inhabitants of the island; for the mechanics who learn their trade in the shipbuilding establishments of the Clyde are among the most proficient workmen in “the trade,” and the wages paid to this class of mechanics being as a rule considerably higher in England than in Scotland, it follows as a natural consequence that many Scotch mechanics come to London. The expectation to meet with the Scottish element in the Isle of Dogs is more than realized, for one of the first things that strikes the visitor is the preponderance of this element, as manifested by the prevalence of the Scottish dialect and Christian names. “Do ye no ken sting’n the wee boy, ye ill-faur’d limmer, ye?” were the first words that greeted my ears on landing on the island on the occasion of my first visit to it, the exclamation having been uttered by a pretty little Scotch lassie about eight or nine years of age, who was in pursuit of a wasp under the impression that it was the same one that had on the previous day stung a “wee boy” whom she had been nursing. As I journeyed into the interior of the island the striking, distinctly-marked Scotch accent and phraseology continued to strike on my ear at almost every step; for owing to the sharp ringing noise caused by the riveting hammers which are at work in all parts of the island for many hours in the day, the inhabitants acquire a habit of speaking very loud when in the streets. And thus the broadly-accented “How are ye?” and the “Brawly, how are ye?” which the gude wives exchange when they meet, and the invitations to come awa’ in (to a public-house) and have “twa penny-worth,” or “a wee drap dram,” reach my ears. During meal hours, and the early part of the evening, when the workmen are passing through the streets, the ascendancy of the Scottish tongue is still more apparent, and Sandy, Pate, and Andrew are the names that are most frequently exchanged as the men from the various workshops salute each other while passing to and from their work. At these times a good deal of chaffing goes on among the workmen, and in this species of encounter, the dry humorous Scotchmen have very much the best of it. But as the burly Lancashire men on whom the Northern wit is chiefly exercised, are as good- tempered as they are big, and the dapper, sprightly Cockneys who occasionally join in the encounter are unable to realize the idea that they are getting the worst of a contest of wit with countrymen, the unpleasant consequences to which chaffing often leads are obviated here.

Of course, in a locality so favoured by Scotland’s children, there is a kirk, and a very comfortable little kirk it is, and equally of course the patriotism of the “whisky” drinkers is appealed to by such public-house signs as “The Burns” and “The Highland Mary;” and it must be confessed that on the island the public-houses are a much greater success than the kirk.

Life in the Isle of Dogs commences at a very early hour, and that “horrid example” in sluggards who always wanted a little more sleep, would have had great difficulty in obtaining it after five o’clock in the morning, had it been his fate to live on the Isle of Dogs. At that hour a sound of hurrying to and fro begins, heavily nailed shoes patter over the pavement, windows are thrown up, and shouts of ” Can you tell us what time it is, mate?” or “Do you ken what time it is, laddie?” are answered by other shouts conveying the required information; while knockers are plied by those who are “giving a mate a call” with extraordinary energy and persistence. By a quarter-past five the sound of footsteps has increased until it resembles the marching of an army, and from that time till ten minutes to six it continues unabated. It then rapidly decreases and becomes irregular. At five minutes to six the workshop bells ring out their summons, and then those operatives who are still on the road change their walk into a run. In the midst of all this bustle rise shrill cries of “Hot coffee a ha’penny a cup,” “Baked taters, all hot,” and “Cough no more, gentlemen, cough no more,” this latter being the trade cry of the vendors of “medicated lozenges.” Before the hubbub raised by “the gathering of the clans” of workmen has fairly subsided, the sharp ringing of the riveting hammers, and the heavy throbbing sound of working machinery commences; and by half-past six life on the island is in full swing. At half-past eight the workmen come out to breakfast; and at that time the gates of the various large workshops are surrounded by male and female vendors of herrings, watercress, shrimps, or whatever other breakfast “relishes” are in season. The instant the breakfast bells ring the workmen rush out through the workshop gates, some hastening to their homes, and others into the numerous coffee-shops in the immediate neighbourhood of the yards. A good breakfast of coffee, bread and butter, and an egg, can be got here for fourpence-halfpenny. Forty minutes are allowed for the discussion of the morning meal. During dinner hour, which is from one till two, and from half-past five till half-past six in the evening (in the workshops that are closed at one on Saturdays the men work till six in the evening on the other five working days of the week, in those where they work till four on Saturdays they leave off work on other days at half-past five), the streets of the island are again alive with the crowds of hurrying workmen. But during working hours the streets are comparatively deserted, save by children, and the numerical force of the juvenile section of the inhabitants of the island does great credit to the papas and mammas, for though the island is generally considered a very unhealthy place, the children as a rule appear to be robust.